|

This is an introductory sample of my next book, a novel, about the relationship between an Adivasi woman and a German missionary woman (my great great grandmother, Doris). Much of this process is thanks to Alpa Shah Alcoholics Anonymous: the Maoist Movement in Jharkhand, India 2010. Modern Asian Studies and Roger Begrich Inebriety and Indigeneity: A dissertation Johns Hopkins University 2013. Let us step into the midst of a 19th century Oraon village in the middle of a much bigger story ....

------------- The following day after returning from market, Singhini began to make a big batch of Mahua Pani. Holi celebrations were to begin soon, raising the demand for Mahua Pani by market people, especially the Dikhu. In the corner of their living space she brought down a large sack that hung from the roof rafters. This was the last of her stash of dried Mahua flowers that she and her daughter had gathered last April. The first year they collected and dried the flowers and stored the dried flowers in the room where the goats and cow were kept at night. But found that the cow was helping herself to the sweet treat by nuzzling her snout under the cover of the basket. They only figured this out when the cow’s milk began to taste fermented and the cow herself began to act very strange. Of course her mother-in-law thought the cow had within it a spirit, but it was Singhini who solved the mystery when she realised most of the collection of flowers had been consumed. So this year she kept the dried flowers protected by hanging them in an old sari in the family room. Throughout the year, and especially in the monsoon months, she liked the sweetness that came from the bag hanging on the beam. A sweetness that filled their dark and smoky home. It had been a very cold night and so she was glad to work out in the sun by the fire. First she made the Ranu mixture of herbs with water; poured it over the dried flowers; covered the large pot with a large flat basket; and finally moved the pot to the other pots piled on top of eachother in the shaded corner of the courtyard. The pot would sit for fifteen days. Among the pots was a batch she had made a few weeks earlier. She checked it, concerned that the cold that night might have retarded the process. The batch had nice bubbles on the top and was ready to distill. By the time the fire was hot she had collected water from the village well. In the first pot directly on the fire she placed the watery fermented mahua flower mixture. On top of that she placed a pot with holes at the bottom to let the steam through from the cooking mahua ferment below. Inside this pot she placed a smaller clay vessel to collect the mahua pani. On top of that she stacked a third pot that held cold water. She didn’t know that this principle to enhance the distilling process was referred to as condensation; all she knew was that for generations her clan had done it this way. Throughout the day she made sure the fire remained hot and that the top pot of water was kept cold; changing it at least five times throughout the day. While watching the pots, she did other chores around the house. Her husband spent most of the day lying in the sun smoking his little tobacco-leaf cigar. Her mother-in-law had stayed under the blanket in bed. Her children were playing with three other children near the well. She watched Urbas keeping up with them as his sister bossed them around. Two of their friends were missing. Had the spirits attacked them in the cold of the night? The thought made her scoop out some Mahua Pani from the central vessel to test it; then she poured a few drops onto the doorstep of their house. This might appease any begrudging ancestral spirit who could be after her family. After a week of brewing, she had many pots to sell at the Melas held in the area that week. The Barra Mela was held every month on the first Tuesday and Wednesday in Gumla, a day walk away. Her husband attached the cart to the village bullocks to carry all the produce from the village including the Mahua Pani made by his wife and other women in the village. The family, including the mother-in-law, left on Monday morning on the ox cart, down a road the British had built. They stopped halfway to visit the family of the mother-in-law’s brother. Feasting, drinking and dancing went on throughout the night. Singhini did not join in the dancing around the Akra, being ever vigilant to watch over the Mahu Pani that it wouldn’t get used up after the host’s Hadia (rice beer) was consumed. The next morning her husband, in a drunken stooper, could barely lead the ox cart to the market. Because of their late arrival they sold very little on the first day of the Mela. The parents and their two children slept underneath their ox cart. The next day was much more successful not only for selling, but also for purchasing some new farming tools and other household utensils made of brass, wood or straw. On the way back they only stopped to pick up the mother-in-law who had stayed with her relatives. Singhini still had more pots of Mahua Pani at home that she wished to sell at the Thursday Mela at a nearby village. Singhini went on her own and sold the wine to other Adivasi. Sales were slow, for most people made their own. But a few who Hindus and Sikhs wanted to stock up their supplies for the festivals. On Friday she returned to the Mela outside Lohardaga with the last pot of distilled wine she had left. She took the large pot and placed it on her head. On top of the lid she placed a straw mat and stacked the patli cups that she had sewn together of sal-leaves. Mani had taken some of the pani and put it in a small pot that she could carry on her head. Her mother said nothing about if her daughter could or could not come along. Urbus stayed willingly with his grandmother. Mani, like a silent shadow, simply copied everything her mother did, and the mother in return provided no advice. Singhini set out among the fields, followed by a half-size copy of her just as the sun was rising in the mist. Singhini was grateful to find a good spot at the Mela, next to the road where she was sure she could sell the wine quickly. She laid the mat down on the floor next to a semi permanent raised stall made of bamboo. Singhini placed her heavy pot carefully down on the mat. Mani did the same, even adding the same grunts and gestures. The glimmer of sunlight reflected off the brass pots piled high on the stall, capturing Mani's attention. The light was wonderful. But then her mouth dropped open, for amidst all these shining objects sat a large-bellied bare-chested man. She had never seen such a belly. “You! You little pig eater! Go away from here!” the man bellowed at her. Somehow he unloosed himself from his throne among the brass pots, shouting in Hindi. Mani was frozen with astonishment until the towel suddenly flew off his bare shoulders and slapped her across the face. Mani fell into the dusty road. Singhini instantly came to her daughters rescue and began yelling back at the man in Kurukh. Mani was almost as shocked by what her mother was saying as she was at the slap. The names she called the man had never been spoken in the village, not even when her mother was angry at her father. The big-bellied man then kicked Mani’s small clay pot and the contents spilled all over the mat, shouting: “Take your foul liquor and leave!” Mani had seen wonder, that soon turned to astonishment, that turned quickly into things she never heard before, but it was this act that made her burst into tears. Singhini turned on her as if she was going to slap the child herself: “Stop! Don’t Cry! You cannot replace one water with another. Don’t waste your tears on such a fool!” As Singhini began to pick up her belongings, she continued to curse the man in Hindi: “We will see who cries now!” Turning to leave with Mani in hand she shot the man such a look that even he turned away and begrudgingly climbed back up on his perch. Mani was too stunned to cry and hugged the rolled up mat and followed her mother obediently. She had never seen her mother give the evil eye. From wonder to disgust to pain to sorrow her emotions finally settled on fear. Her mother was to be feared. Singhini approached the center of the maidan thinking she could join the other Adivasi women selling vegetables. But the women’s tongues began to call out to each other: "Look, this is the one who only the Gora Memsahib will talk to." "What is so special about her? Oh she has a lame child? Chee..." "Look, she comes to sell us pani as if we do not have our own." Singhini kept on walking. At the far edge of the field of vendors she settled under a tree to sell what was left of the fruit of her labor. It ended up being an excellent spot. Various Dhikus, Jains, Hindus and Muslims, who feigned to never touch the stuff, hid behind the tree to purchase the coveted booze. Handing her their bottles to fill, they stood off to a distance acting aloof. Mani held the bottle and Singhini carefully filled them. Then they returned behind the tree to finish the transaction. By midday she made the last sale to a red-eyed man who then as if drooling, asked if the little girl was also for sale. This soured all Singhini’s feelings of vindication of a productive morning of sales. Singhini’s whole body shuddered at the disgusting proposal. Quickly she wrapped all her money in a red cloth and hid it in her blouse. Picking up the empty pot, she slung it under her arm, and rested it on her right hip. Mani had rolled up the mat, Singhini tossed it on top of her head. Grabbing her daughter’s arm with a tight grip, she dashed out of the Mela, as if she was running from a tiger. Out from the field of vendors she reached the road and freed Mani’s arm and returned to her usual pace. From the grove of trees alongside the road, she heard a strange sound. It was like the sound of a mating bull, but rhythmic. Forgetting the feeling of fright and disgust she had just felt, her curiosity took over, and she walked through the grove of trees to join the crowd gathered around such strange music. ----- Modern story of the brew written and video:

https://www.brewer-world.com/desi-mahua-beer-from-india/

https://youtu.be/RlIuCPAci8E

1 Comment

Here is what Ferdinand Hahn wrote as recorded in Introduction to the Kols Mission Field, by Ferdinand Hahn.Part 3 - The Religion of the Kols. Chap. 15. The Understanding of the Kols about the Highest Nature. as translated by Theodore C. Feierabend (unpublished 2019)

It is the Oraon, however, who worship the most ardently, that the earth may be fruitful. At the Khaddi festival, also called Sarhul, in the spring, when the sal-tree begins to bloom, they celebrate the marriage of Dharme with the earth. The former is personified by the village priest, the latter is identified by the elder of the holy grove. The Korwa hold the Mother Earth, the Dharti-Mata, as the supreme deity, who dwells in the sacred grove under a sal-tree. They perform sacrifices for the grain to flourish. Thus, too, the Oraon imagines the earth as one with the spirit under the sal-tree, the Jhakra borhi. The meal between her and Dharme takes place in the following manner: The village priest, together with his wife, fasts at the beginning of the festival, on the eve of the same. Then, accompanied by his assistant, he goes from house to house through the whole village. Each housewife gives them some hands full of rice. The priest keeps about half of it, and the other half the priest returns. Through this symbolic action the main food is blessed. Of the returned rice, the women hide some grains in their house, and when it grows, it is a good sign of a rich harvest. On the evening of the first feast, the priest, with the help of his assistant, takes a new large earthen vessel, filling it with water, and carrying it to the holy grove, where he places it at the seat of the god, the certain ancient sal-tree. Such vessels are porous, and therefore lose content, even if they remain only one night in the open. It is now very important that very little water is lost during the festive season, as this is a sure sign of a good rainy season, which is so important for the prosperity of the crop. Thereupon the priest takes a sacrifice in the presence of the villagers on that tree, consisting of two white hens, some vegetables, rice, oil and brandy, and, last but not least, cinnabar, with which he bites a twig of the sal tree with a piece of zeng or a cotton thread, then brushing his chest, his forehead and his ears, and thus marrying himself with the tree; the representative of the sun god being the tree and the representative of the mother earth residing in him. Thereupon the priest prays: “O Old One, bring forth the fruit of this year. May the rain fall, so that the corn may grow and flourish." As the bridegroom and bride are carried to the village or dwelling-house, the priest is now carried into his house. Then he visits all the houses again, and distributes sal-blossoms, which the women use to decorate their houses. Then they wash his feet and give him rice and money. His assistants sprinkle the roof of every house with water to indicate that now rain and fertility will follow, and finally dining, drinking, and dancing, as is customary at weddings, with all shame and good manners being laid aside. In the case of the Ho, this feast is celebrated in a particularly exuberant manner, although they lack the idea of combining Singbonga with the earth. The Santal and Munda also have their seed sacrifice and feast, which they call Kadlo-Sa. From my Blog: wwwjourneyfromjourneyto.com December 2019: Christmas thoughts from Mary Girard I was so blessed when Joy shared this picture on Facebook. Though I had studied art under the Christian Indian artist, Frank Wesley, and have a book of his work, I had never seen this one. It clearly is his work; incorporating the message of God among us (Emmanuel) in the classical Kangra Valley style with Indian symbolism. I just love the fact that there are hardly ever nativity scenes where baby Jesus is in the arms of Joseph. As I care for my aging father I am more and more aware of the important role of the active father in a child’s life (from infancy to the end). Enjoy meditating on this picture and reading the comparative birth stories in Matthew and Luke this Christmas season. May new insights of love, joy, peace and hope be birthed in you in the midst of a world; that is on one hand as beautiful as this, but on the other hand is just as cruel and oppressive as it was in the time of Jesus. This past year has been so rich. I published my first book (through Lulu.com) and have had a few opportunities to promote it in the US and India. As I await efforts to get the book published in India (after a careful edit) I will continue to promote the publication in the US and Europe this coming year (starting in Florida in January) For those of you who have had a chance to read it I would appreciate if you posted your candid reviews on Amazon, Lulu, GoodBooks, Barnes&Noble or where you might have purchased your copy. My goal is to increase sales of the book in the West by 3 fold. And when I say “candid”, I mean that. This was a challenging book to write. There were so many varied readers who I wrote for: academics, Christians of various ilk, those concerned with social justice, history, psychology and culture, as well as the Adivasi themselves and the general Indian population that see afresh their own history. I’m bound to step on a few toes or to confound others. I already know that some readers have found the book has spoken to them on an emotional or mental level. My main hope is that it ignites thought and even conversation about our complex world and histories and that the cause of the Adivasi and Christian minorities in India will be known. I was very happy to attend the Jubilee Centennial year of the Autonomy of the Gossner Church (Evangelical Lutheran and 90% Adivasi). It was wonderful to join the churches in celebrating their culture, community, history and their Lord. Celebrating in November with GELC in Ranchi Glad to share the joy and adventure of this trip Glad to meet Klaus Roeber, a cousin. His with Delia ancestor was Gossner Missionary Alfred Nottrott I also enjoyed speaking to many groups in India about the process and reasons for preserving and learning about and from their heritage and the unique Adivasi history. It must be documented or written down as the oral agriculture-based culture is perpetually diminished. On my next blog post I will share more details about the writing workshops that I have done and plan for the future.

I also enjoyed visiting Chhattisgarh for the first time since 1976. Since the monsoon was lingering everything was so green and fresh. Though I have little personal memory of my childhood home (ages 1-5) there are many family memories that were revived by my visit. Some readers have commented that the family story in Among the Original Dwellers is very sad. It is true that my ancestors sacrificed their family for the sake of a higher calling and the ramifications have been felt by their descendents. Yet I cannot help but think that the tragedies of history present to every generation a choice to choose a better path, by learning from the lessons of the past and working through the family pain. My cousin* who wrote in German about her great grandfather (Hans in this excerpt below) tells that despite the sorrow he felt as a child, his parents helped him find his way in an ever-changing world. * Seele, G. - 2008 - Der eigene Weg: Hans Hahn und seine Freundschaft mit Waldemar Bonsels (The One Way). Are there not some places where we seem to breathe sadness? - Alexandre Dumas

In March 1894, the Hahn family headed out to Germany on their second furlough. ... Doris packed up all their belongings, not sure if they would return to Lohardaga. She hoped they would, because she had invested so much into the lives of the women and those suffering from leprosy. Much could change in the eighteen months that they would be gone, and they had to be willing to go where they were needed when they returned. Once their accumulated belongings were stored away in a godam (warehouse), she turned her attention to reuniting with her seven children in Germany. They traveled with one trunk for their travel needs and another trunk full of saris, shawls, brass utensils and other decorative items that would be gifts from India for family, supporters and hosts along the way. Again, they chaperoned a gaggle of missionary children and their luggage, including their rambunctious sons, Heini and Gopa, and toddler daughters, Dorle and Lieble. Each child carried a satchel with their own personal items, toys, books and their own personal brass cup and plate for the journey. ... They arrived at the Gutersloh Station on Easter weekend. Waiting on the platform were Johannes and Albert (or Hans and Bertie as they were called by their friends.) Would the parents recognize them? Johannes was a lanky teenager and Albert was taller than when he left home, three earlier. In the beautiful sunshine, among the spring flowers, the boys stood waiting on the platform, their hearts storming with emotions. The boys wondered if their parents would be as odd as the missionaries who visited their school. Upon seeing his father, hannes thought, his appearance was not so exotic or unkempt as other returning missionaries had been; he seemed a gentleman with the superior assurance of a man who had seen the world. Ferdinand jumped off the train to greet his boys with firm handshakes and pats on the back. He noticed the tightness in their shoulders and the weakness in their hands, so he grabbed their heads and brought them to his chest, hugging them as he rustled their hair. This annoyed the boys who quickly scrambled up into the train compartment straightening their clothes and hair. They found him perhaps a little too good natured and light hearted. On entering the compartment, they noticed a woman, who must have been their Mother, dealing with a swarm of strange children. Eventually she rose and smothered them in hugs and kisses, which Johannes resisted and resented. Doris was taken aback by his juvenile behavior. What did she know of the modern teenagers? Gone were their carefree ways and innocent trust. A darkness had grown in their wounded hearts. After having traveled halfway around the world, far from home, the seven-year-old boys’ sense of adventure quickly dissipated. Their parents’ attempts to prepare them for Germany, had not prepared them for loneliness and strangeness. They succumbed to the efficient orderly piety that folded in around them like grey clouds. Bitterness and abandonment were planted in their young hearts and minds. Guilt overwhelmed Doris, seeing them so timid and cold toward her. She realized she had abandoned them, but when they had left Lohardaga, she only thought about how abandoned she felt. Ferdinand had discouraged her from getting overly emotional about their departure. He framed every difficult experience as an exciting adventure. Doris now felt she had sent them off to war and they returned wounded. They spent Easter together in Bielefeld, but time was too short to undo the harm. Doris insisted they keep their home base nearby in Bielefeld when the children returned to their respective schools. She was desperate for more time to bond with them again. Much would be healed during the summer holiday in Uetersen. She trusted that the Lord would gather and bind up the broken hearted (Psalm 147:3). That summer, when their eldest son,Theo, visited from America, he confided to his parents that the boys were not thriving in the well-meaning care of the Wuforst family. He confessed that his brothers were only following his poor example, putting up appearances of good behavior while behaving like hooligans. Unfortunately, the Hahns could not afford alternative arrangements. What family would take four boys, now that Gottfried and Heinrich were also starting school? The delightful Bonsel family, at the Bethel school in Bielefeld, empathized with the family's plight and offered to keep an eye on the boys. The siblings often stayed with them on weekends and holidays, so they could be together while the parents were away. The parents thought their daughters were less wounded. Perhaps they hid their wounds better. Frieda and Gushie attended the girl’s boarding school in Bielefeld. Dorle and Lieble would not start school for another five years. Louise and Mietze, now in their twenties were eager to return to work in India with their parents. In May, Ferdinand traveled again to Great Britain to raise support for the Leprosy work in India. While he was there a notable book by Rudyard Kipling hit the bookstands. He bought a copy of The Jungle Book for his children, so they could take turns reading it over the summer to practice their English. He began reading it as he traveled back to Germany. He felt Kipling’s allegorical style captured the issues surrounding race, place and identity.409 Like Mowgli, Ferdinand felt conflict between his German self and the part of himself that identified so intimately with India and the tribal people. He could relate to the song sung by the young boy: "As Mowgli flies between the beasts and birds, so fly I between the village and the jungle... These two things fight together in me as the snakes fight in the spring... I am two Mowglis.”** Ferdinand recognized that he felt like two persons within one body. He also had seen this tension among the Adivasi Christians, as they struggled with both their identity as Adivasi and as Christian, in an environment that was antagonistic to both. Now for the first time he thought about how much more his children must feel this tension. He hoped Christ would be their anchor in this ever-changing world, while giving them wings to sail above it. But it seemed their wings had been clipped. They struggled to fit in to a European society, that had become more rigid than Ferdinand remembered, and it left an ocean-wide gulf between him and his beloved children. He resolved to provide them with support and the counsel to endure. When summer holidays began Ferdinand decided to limit his travels so that the family could enjoy the precious and rare occasion to be together in Uetersen, where Doris’ uncle was the only member of the Voss family remaining. ... Ferdinand hoped to plant seeds of encouragement into their impressionable hearts and minds. ** Waterman, Anna - January 2016 - Perceptions of Race in Three Generations of The Jungle Book. A similar language of split or multiple identity can be found in W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1903 theory of double-consciousness, the condition of being raised in a European/ American setting, but African by [descent]: “One ever feels his twoness: an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

Louise (Hahn) Nottott with Maya (my great grandmother and grandmother_ Louise (Hahn) Nottott with Maya (my great grandmother and grandmother_ When those of the Oraon tribe were asked what they called themselves, they replied: En Kurukhan or "I am a speaker," as opposed to one who cannot speak Khurukh. Ferdinand found this like how some European tribes identified themselves. The Slovenians call themselves Slovo (word), and they call Germans Niemzi (mutes). Essentially, you are what you speak. Ferdinand may have lived in the jungle plateau region of east India, but he never stopped being German. What made him German was his mother tongue and his connection to the land of German speakers. A land of diverse ethnic groups and tribes that were considered Germanic from ancient times, reporting back to the 2nd century BC and extending into late antiquity to the Middle Ages when Christianity came to the land. But here in this jungle region, surrounded by other languages, a cross-cultural identity was being created within him and his children.[1] Except for the occasional German visitor, the only German spoken in Lohardaga was among family. The Hahn children had to learn the German language, culture and history so that they would be ready to go to school in Germany when the time came. Ferdinand taught the oldest children: Louise, Mietze and Theo. Teaching his own mother tongue made him aware of the complexities of language, as he compared and contrasted German, Hindi and Kurukh. In Kurukh all irrational existences have neither gender nor number. There is a form to denote plurality in neuter nouns; but when verbs are conjugated the noun is then treated in the singular. Women in the singular appear to be feminine but in plural are male...[2] In German, on the other hand, there are three gender markers in the singular: der (masculine), die (feminine), and das (neuter); the definite article, die, is used in the plural. English, which also was taught to the children, uses only one marker for the definite article of all nouns, namely “the.” Hindi doesn’t use articles, but it has gender indicators. For example, kursee (chair) is feminine because it ends in “ee”. Kurukh is the simplest, it doesn’t have articles, and objects do not have gender. Ferdinand reasoned over such distinctions, but his children naturally knew the application of gender for each language. Then when he taught them numbers in German, both the cardinal and the ordinal, up to ein Milliard he noted that Kurukh had no conception of a hundred let alone a million. Ferdinand asked his children: “Did you know there are only two numbers in Kurukh: singular and plural? In fact, in Kurukh number and gender are only given to rational beings”[3] Seven-year-old Louise asked what was a “rational being.” She was told humans, God and spirits, and maybe a few animals. Something that feels or thinks. She questioned her father, “But Papa if something does not think and feel, do we need to count it? Does anything need to be counted?” She didn’t like learning numbers, but she also could not explain why she didn’t like being asked, for example, “How many mangos are in the basket?” Or “How many people live in our house?”[4] Her father thoughtfully replied that it is important for organization and development to quantify and evaluate things and people. “We must know the number of members of our church, for example, so that we can know how best to serve them, and where to put resources.” Then he added with some annoyance, remembering that the accounts of the church had once again not balanced, sighing, “But then some never seem open to progress and are simply too stuck in the mud.” Louise could not understand why her father was annoyed. She didn’t think it was about anything she had said, so she ventured to ask one more question. “Papa, isn’t that a good thing?” “What do you mean, child?” Ferdinand asked. “To be stuck in the mud. Isn’t that a good thing?” Ferdinand laughed, recalling that Sulaman Khalkho once corrected him about the meaning of such an expression, “For the Adivasi the image of being stuck in the mud means the person is rooted, and unshakably committed to his community. I know for you it means the person is stubborn, but for us this is a good thing.”[5] His daughter must have overheard that conversation. She seemed to be starting to think like an Oraon. Her question had been more profound than she understood. She may not have understood why her last question was left unanswered, but she felt proud that she had made her father happy as he repeated to himself, “Out of the mouths of babes.” see also: http://www.journeyfromjourneyto.com/writers-journey-blog/language-identity-perspective ---------- [1] “Third-culture identity”, Pollack and Van Reken – 2009. [2] My paraphrase FH – 1896. [3] Ibid. [4] During a visit in Ranchi I overheard a German ask an Adivasi if they knew the population of India, to which the person replied, too many. I do not believe this was a matter of lack of knowledge, but a cultural characteristic among the Adivasi reluctant to quantify anything. I attended several large gatherings and was often told that there were 5,000 or 10,000 people in attendance, with an added comment “like when Jesus fed the people.” Those numbers are representative rather than quantitative. [5] Bishop Nirmal Minz told me the Adivasi interpretation of this expression. Much of my career in the world of nonprofits has been to promote mentoring. Here is the opening chapters that features a mentoring relationship that impacted Ferdinand Hahn's life. From the parsonage at the top of the hill the new Superintendent of the Ketzin Evangelical Lutheran Church, the Reverend Knuth, was observing the troubled teenager lying alone under the pear tree. He had previously tried to reach out to the boy, but Ferdinand evaded everyone after his failed escape. The pastor walked down the hill and approached the daydreaming lad with caution. If he could, he hoped to offer the young lad friendship, guidance and encouragement – whatever would be received. The quiet crunch of his steps upon the grass interrupted Ferdinand’s wandering thoughts. The boy was startled by the round-faced bright-eyed pastor and dreaded receiving a long-winded sermon. Instead, the Pastor sat down next to the boy on the grass in silence. The pastor was a new arrival in town and began asking about the Havel river and Ketzin. Ferdinand was surprised by his friendliness. No elder in town ever asked him inquisitive questions or shown him any authentic empathy. Something stirred within Ferdinand’s heart. Uncharacteristically the lad sat up, straightened his hair and addressed the community leader with respect. He noticed that the pastor's jacket was worn and loose, as if he didn't care so much about appearances. Even though the Pastor was not comfortable sitting on the grass, he settled and attentively listened as the boy told about the river’s ebbs and flows. As they continued to talk about a variety of things, Ferdinand found, for the first time in his life, an adult genuinely interested in hearing his dreams, fears, and burning wanderlust. From that day on, Ferdinand was welcomed into the pastor’s home. It became his first haven of hope. In entering the cleric's library, Pastor Knuth widened his arms to draw attention to the walls covered in books: “Here lies your world to discover. I welcome you to find in these books your adventure, your education, your destiny.” Thus, began the young Ferdinand’s enlightenment. The teen browsed the bookshelf noting the gold-etched leather bindings of authors: Hegel, Goethe, Schlegel. The son of a Prussian shoemaker browsed the pamphlets scattered on the desk. More unfamiliar names: Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, Philipp Jakob Spener, and Johannes Evangelista Gossner. He would become familiar with all that was housed in these books — idealism and alienation, history and romanticism, philosophy and theology — a strange yet rich intellectual and spiritual garden. Ferdinand’s overbearing father accepted the charity extended by the Pastor to tutor his son. The arrangement permitted the troubled lad time to study at the parsonage after first fulfilling his duties in the cobbler’s shop every morning — except for the Lord’s Day of course. The father’s only expressed ambition was that the boy be confirmed. Perhaps the pastor could also bring his son around to repentance and make a good Christian of him. Ferdinand Karl Philipp Hahn received his Confirmation on a foggy Sunday after Easter, 15 April 1860. His preparation reviewed basic Christian doctrines, church authority, the Sacrament of Baptism, and Confession, the forgiveness of sins, and the Eucharist. The Luther’s Catechism was designed as a series of questions and answers. Ferdinand was encouraged not just to memorize, but to consider the questions, and even ask his own questions. Ferdinand appreciated being encouraged by Pastor Knuth to think about the meaning of everything. The host of artisan witnesses present at the ceremony were content that he recited the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, and the Lord's Prayer. The ceremony was meant to represent the opening of mind and heart to God, but Ferdinand confessed later that he merely professed Jesus on his lips and endured the ritual in a fashionable and legal way. Pastor Knuth, who had seven grown daughters, viewed his new student as a son. Under his patient and jovial tutelage, the senior cleric provided Ferdinand an extensive education in the humanities and sciences as taught in the Gymnasium. He introduced Ferdinand to the study of language: Greek, Latin, French. Ferdinand absorbed everything. The old Pastor believed his future was full of promise. Ferdinand had his doubts. Provincial life would always hold him back. He began to wonder if his father was right, if there was any use in education if all he could ever be was a shoemaker. One snowy evening, Ferdinand sat down next to the warm fire in the library, warmed by a hot cup of chocolate. The Pastor loved to tell stories that put most of his parishioners to sleep, but Ferdinand loved to hear his drawn-out tales. “The Sounding tree, the talking bird and the golden water were three things the king needed to build a magical garden. I think you are like the many people who have gone in search of these,” Pastor Knuth began. “Most people don’t find it. But listen to this tale and you tell me if you will be among those who discover the mystery of life.” The shoemaker of the village wanted to please the king, so he went to find a wise old hermit. When the shoemaker asked about how to find the sounding tree, the talking bird and the golden water, the old hermit replied, “many have come to me with the same question, but no one has returned, because they did not do exactly what the bird told them to do.” The shoemaker promised that he would do as the bird told. "Take this road," said the hermit, "and you will hear the sounding tree." And, in fact, after three days' travel, the shoemaker heard the sounding of the tree. Before he came up to it, he had to pass through a great heap of stones that had the form of human beings. Figures that reminded him of people who had left his village, the old milk-maid, the blacksmith, the gardener. Then he heard a voice call, "Good morning, what do you want?" He looked around and saw the speaking bird on the sounding tree. "It is you I want," said the shoemaker, "and the sounding tree and the golden water." The bird said, "Break off a bough and take me with the basket down from the tree. Then go to the rock over there, there lies a key. Take the key and open the door in the rock. With the vessel that you will find in the rock, take of the golden water, and when you come out of the rock, do not look behind you, but go straight on." The shoemaker went and did as he was told, but as he came out of the rock, the men-like stones came after him, and cried, "Brother, take me with you." Hearing the noise, he looked around, and was changed on the spot into a stone. When the shoemaker never returned, his son set out on the road and came to the hermit, and asked the way to the sounding tree, and if his father had passed by that way. "Yes," said the hermit, "but he cannot have done exactly as the bird instructed him to do, and so he has not come back." "What road will I have to take to come to the sounding tree?” The hermit showed him the way and gave him the same directions as his father had been given. After three days, he heard the tree sound, and came to the stones. Seeing the stones, he thought they were men, and touched them, but they were only stones. The bird wished him good morning and asked him what he wanted. "You," he answered, "and the sounding tree, and the golden water." Now he had to do the same things as his father had done. When he had done so and stepped off the rock, one of the stones made a fearful noise, and cried, "Son, take me with you." But he went on, taking no heed of the noise, though it grew louder and louder. However, he was so frightened that he fell to the ground. When he recovered, and rose, he saw all those who had gone before him now standing around him, released from stone. Together they returned to the king and placed a branch of the sounding tree in the ground, placed the bird on the branch and a bowl of the golden water next to it. They could not see immediately any change in the garden until the next morning. When they woke, the whole garden had transformed into the most beautiful garden in all the lands. Pastor Knuth reiterated the moral of the story, “don’t get distracted, my son, and you shall find your beautiful garden. Your studies are the gateway through which God will lead you.” “This is simply a fairy tale,” Ferdinand complained. “Very well then,” the Pastor went on, “let me give you an apt example to show you what is possible to move beyond the stone figures that imprison you.” He proceeded to tell a story about the man who had mentored him when he was young in Berlin, Johannes Evangelista Gossner. This pastor taught that it was every Christian’s duty to live a life of service; one didn't need academic knowledge to meet the needs of people or share the liberating message of Christ to others; anyone could be a leader with the power of Christ in their life, following the disciplines and teachings from the Bible. When Gossner was sixty-two he intended to retire as a pastor and focus only on managing the Elizabeth Hospital that he had started. But man proposes, God disposes, and Gossner soon found himself embarking on the greatest enterprise of his life. In 1835 he was approached by twelve artisans who wanted to become missionaries. No regional mission would accept these uneducated working-class men. Since Gossner was vocal about the inappropriateness of studying Homer and Ovid for preaching the Gospel, perhaps he would train them. Moved by their devotion and faith, Gossner began to train the working men two evenings and a Sunday afternoon each week in his home. He taught them about how to use two basic tools for teaching others about Christ: The Bible and the Hymnbook. Then he sent out these artisans—stonemason, carpenter, blacksmith, weaver, tailor, shoemaker, butcher, gardener and bookbinder—to Australia. Others came to him with similar requests, so Gossner established a Mission School in Berlin. Gossner wasn’t against learning, he believed in practical education that was centered on community. Students were taught by volunteers from the community, in the Bible, church and mission history, geography and Greek and Latin (useful for reading the New Testament in the original tongue). Candidates, with active spiritual faith, continued to come from the artisan classes. Gossner hoped his students would be hired by European mission societies to work in Europe or abroad. However, few mission agencies were willing to employ his students, so he was compelled to start his own mission agency. Hundreds of men from all parts of the German speaking world, from every class, subsequently ventured out to foreign lands to spread the good news of God’s Realm. Even though he didn't have a lot of faith, this story rekindled Ferdinand’s longing for adventure and he began reading everything he could about missionaries. By candle light at night Ferdinand engrossed himself in reading JC Wallman’s Leiden und Freuden Rheinischer Missionaire or the Hallesche Berichte. A fresh new perspective in these narratives described life — that is the Christian life — as disciplined, pious, a test of moral rectitude, a search for spiritual purification, difficult but attainable. Everything unimaginable was possible, requiring but the littlest faith. These eighteenth-century missionaries were the primary source of the special knowledge of India in Europe. Eventually such knowledge ended up in the tight grip and perverse curiosity of academic philologists. These “experts” on India, however, never left the comfort of their libraries. Already Georg Foster had set the German literary world aflame with the translation into German of the ancient Sanskrit play Shakuntala, an amazing simple story, written well before Christ, portraying the complex relationship between humanity and nature. Ferdinand was curious about the mystical Orient and intrigued with what he was learning about basic humanity. Having no access to academic discourse, he settled for reading about these so called “dark heathen lands.” At times they seemed as devoid of hope as his own homeland, however, the annotations of strange terrains and diversity of plants, animals and people was mysteriously wonderful. The missionary moved the interplay of earthly and theological concerns out of the theoretical into the context of practical experience. Issues of Man, God, Sin and Salvation were discussed in the context of various faiths. Incredible projects in linguistics, ethnography, and religious studies, and social and religious service made up the missionary life. As Ferdinand’s perspective of himself, his people and the world expanded, he recognized the privilege he had over others to be able to see beyond to a greater world. Though he was poor, through charity he had been given so much. As an Indian proverb in one of the journals said: "When someone gives you charity, don’t consider him obliged to do so always. Use it to your best, as the coconut tree uses the water within to its growth, and to bear fruit after." Ferdinand did not need to have seen a coconut to understand. He wondered how he would “use the water” that he had so generously been given.

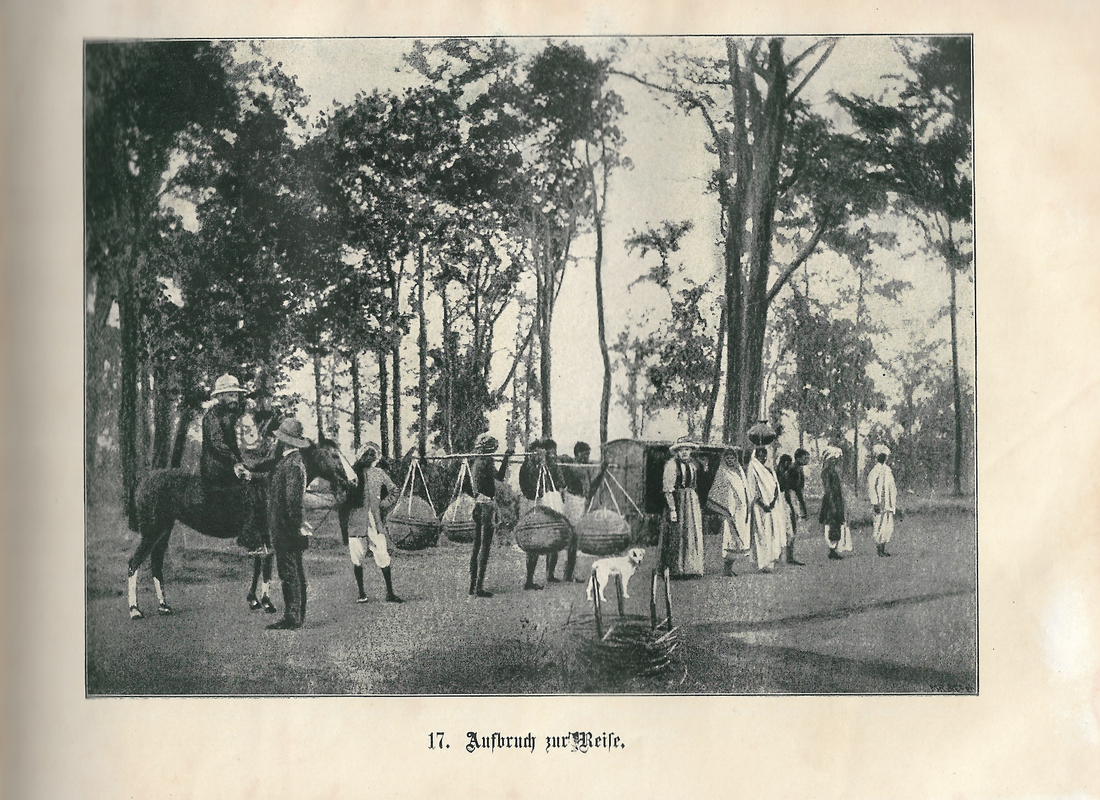

A sample of the cross cultural relations that existed between the missionary and the original dwellers (Adivasi).  Ferdinand Hahn moved his family from Ranchi to Lohardaga to replace Missionary Lorbeer who already had moved to Ghazipur to the north. The departing missionary had grown weary of the isolation and challenges of the Lohardaga mission station and moved north to revive the Ganges Mission. Ferdinand came with every intention of leaving his preconceptions behind to start afresh in his new endeavor. An entourage of porters carrying all the Hahn’s worldly belongings journeyed along primitive paths through the forest for two and a half days. Doris and the three small children were carried in a pulki. Ferdinand walked about a third of the way, when the terrain was too difficult for his horse. The Adivasi porters sang the whole distance or shouted to each other. Ferdinand thought they must be telling each other crass jokes the way they laughed as they walked freely along the way. Periodically they came upon an opening in the woods and a village surrounded by terraced fields. At each village a new group of men carried their belongings and traveled with them to the next village. This was an age-old tradition among the Adivasi; a reciprocal system using labor in exchange for goods and services. The generosity shown to help a traveler or person in need was never a matter of obligation, it was a matter of reciprocity. Co-reliance sustained the Adivasi peoples for centuries and their most precious jal, jungal, jamin (water, forest and land). This age old practice was easily exploited by the outsiders such as landlords and the English, who were masterful in turning reciprocity into obligation. People who were outside of the money economy were forced to pay tariffs through all kinds of work. Ferdinand of course paid his porters what he could. However, because he did not have much money, he soon came to rely on this system of reciprocity and mutual exchange. Lohardaga was full of promise. Life was quieter and simpler. Doris Hahn was glad to be free of the petty squabbles among missionary wives. Their home had earlier been a converted stables that belonged to a British officer twenty years ago. The Lorbeers had turned the stables into a comfortable home. Ferdinand dreamed that one day he would build a new bungalow with more rooms for his growing family. Local Oraons worked alongside them to assist most generously in helping the new missionary family settle. To secure beams when fixing the roof, they produced a strong rope made from grasses. They suggested where supplies could be obtained and how to prepare for the rains. In exchange the workers were given a modest meal for their services. The Oraon women showed Doris how to utilize the outdoor kitchen, covered by a thatched roof and two mud walls. Most of the room was taken up by the dheki, rice pounder. They taught her how to pump the long wooden beam, balanced on a fulcrum, with her foot, so that the “hammer” on the other end would pound the husk off the few handfuls of rice lying in a hole in the ground. |

Details

Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed